Completed in 2019, Robin’s Nest is one of the most visible and complicated projects b9 architects has ever worked on. As the former site of the first Red Robin, a Seattle institution, and being vacated since 2010, the site holds a unique place in the community. First as a local institution, and second as infrastructure, acting as both improvised parking for adjacent residences along Portage Bay, and as a pedestrian path down the slope from Fuhrman Avenue to the water. During the design and permitting process, b9 architects committed to exceeding the goals of our client, satisfying the desires of the community, and responding to the guidance of the Seattle’s East Design Review Board.

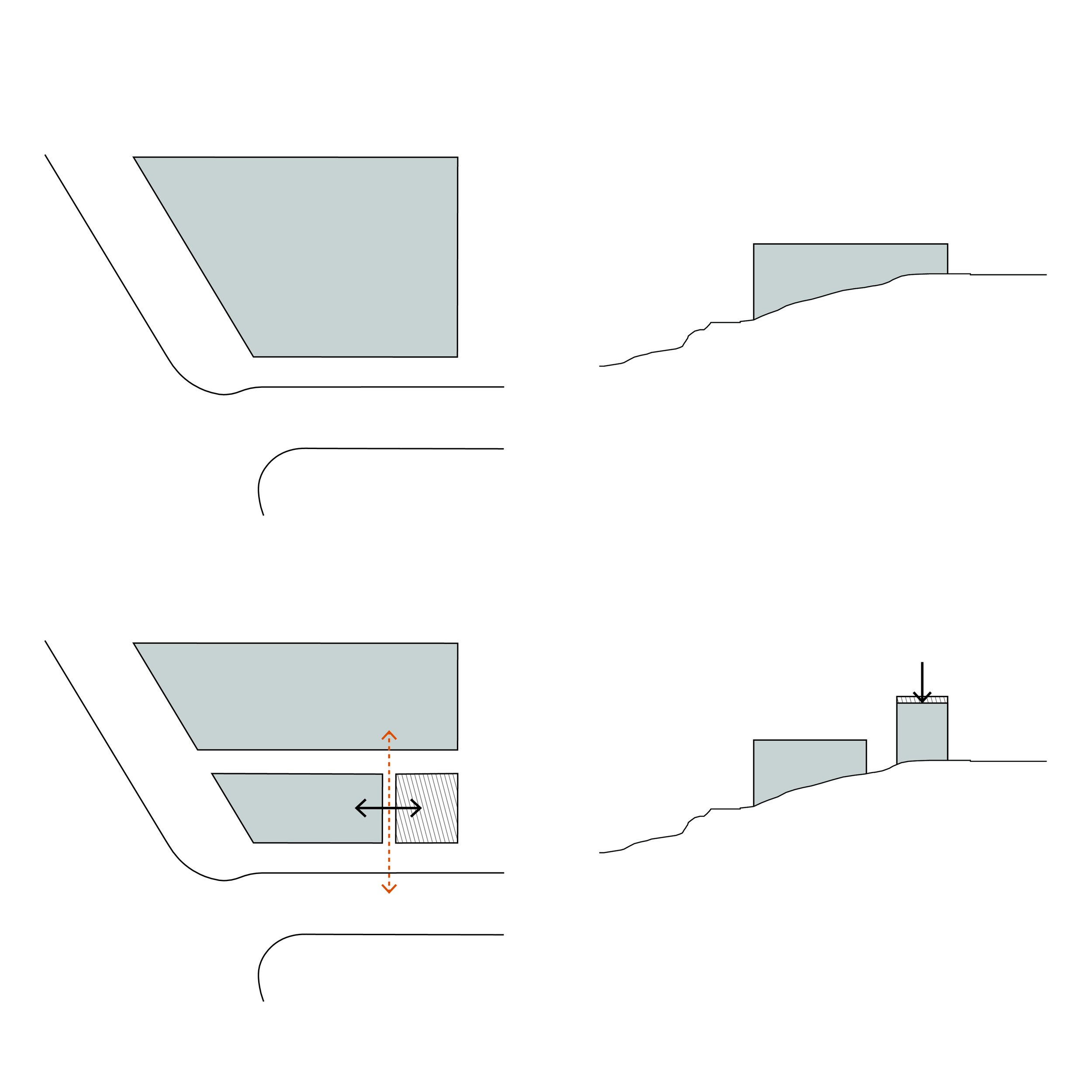

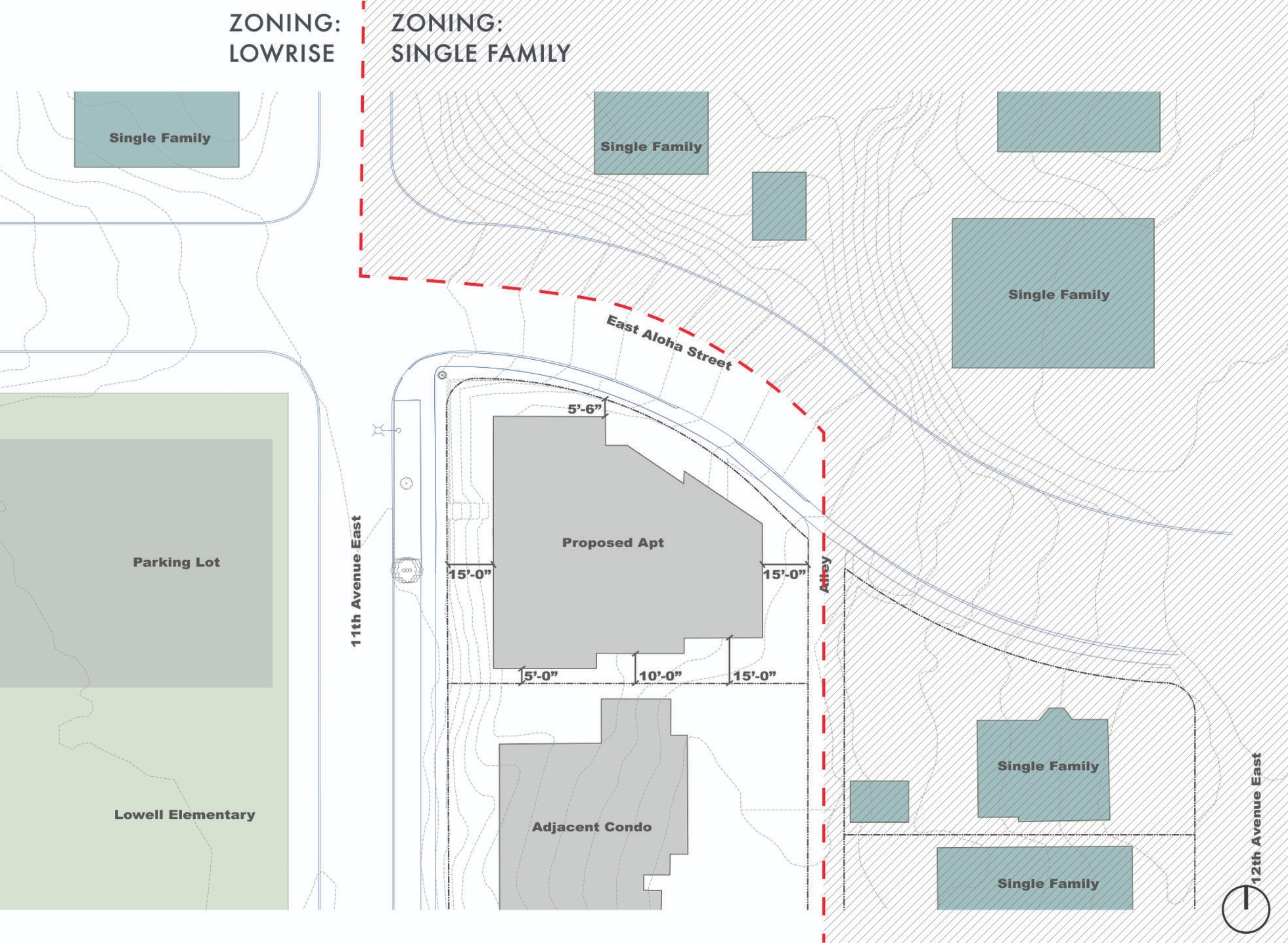

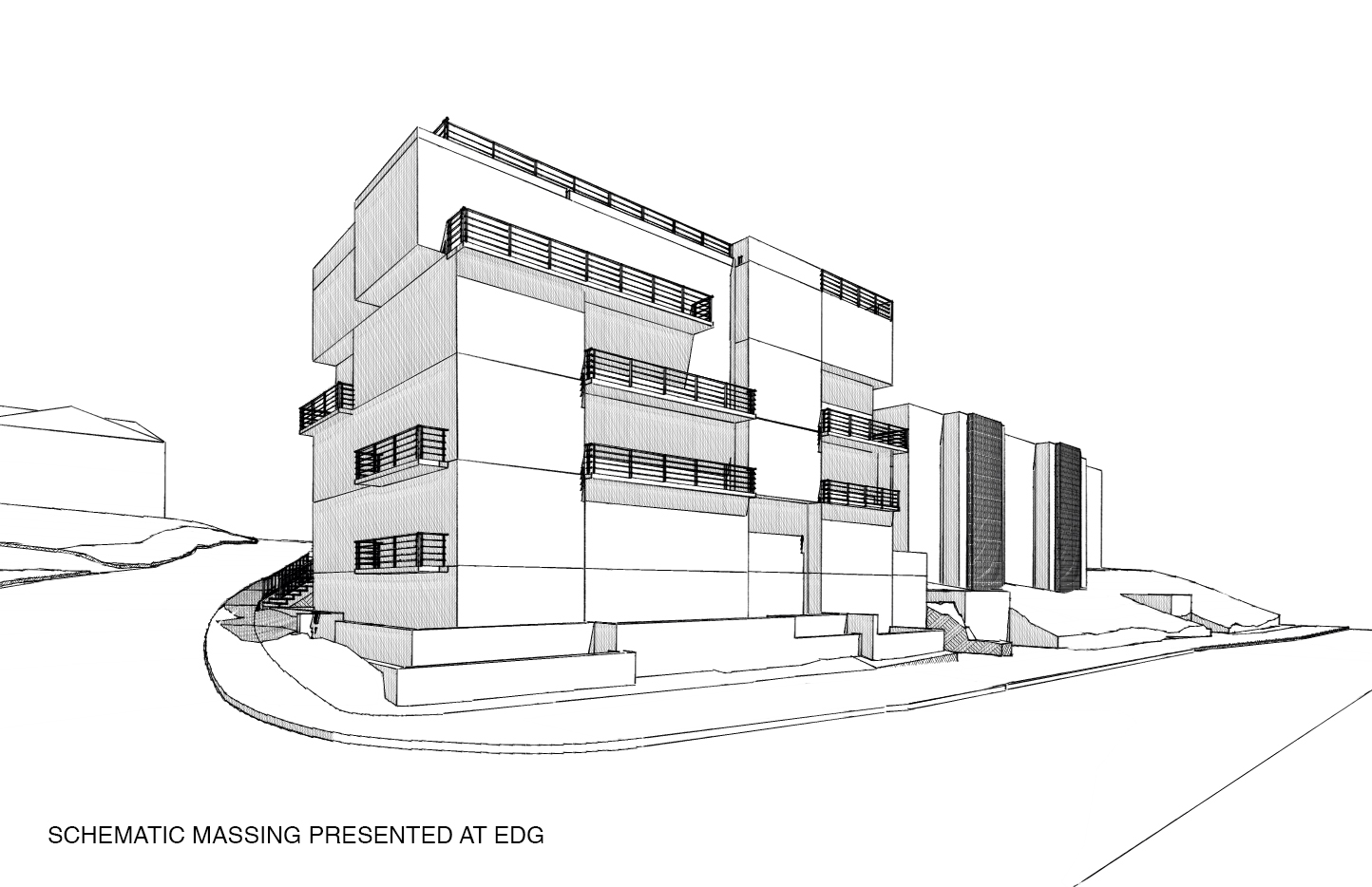

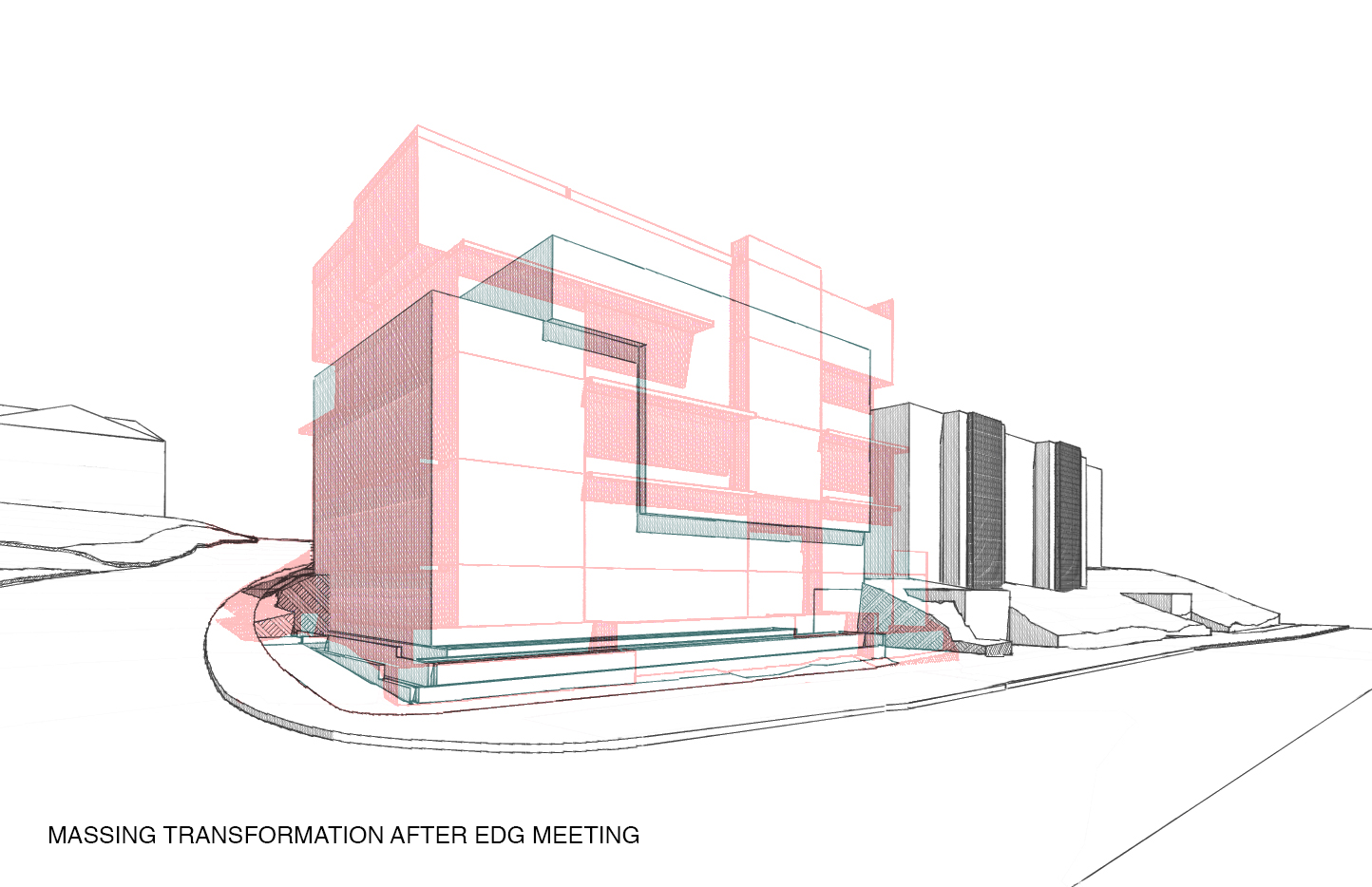

From the outset, the client and b9 architects were on the same page: for a project at this particular site, the biggest priorities were balancing excellence in both design quality and maximizing the potential of this important site. The site’s sloping topography and proximity to the Portage Bay shoreline altered the way we approached the design. The intersection of Fuhrman Avenue E and Eastlake Avenue E at the southern exit of the University of Washington bridge, is highly trafficked and prominent. It was important to both the design team and the Design Review Board, that the corner of this site achieve a scale that matched the other structures on that intersection. Unfortunately, due to the proximity to the shoreline, the expected height limit was reduced by 10 feet. In addition, the height measurement technique in the shoreline was designed to limit the amount structure height at the highest part of the sloping site, thereby threatening the desired scale at the corner. b9 proposed a solution; instead of a single L-shaped building that would address the corner and front Fuhrman Avenue E and Eastlake Avenue E (University Bridge), the design evolved to an unexpected solution. By splitting the project into two distinct structures, the corner structure could capture the full height limit while a second structure that wrapped around the north and east edges of the site could step down the grade and respond sensitively within the bounds of the shoreline’s height limit.

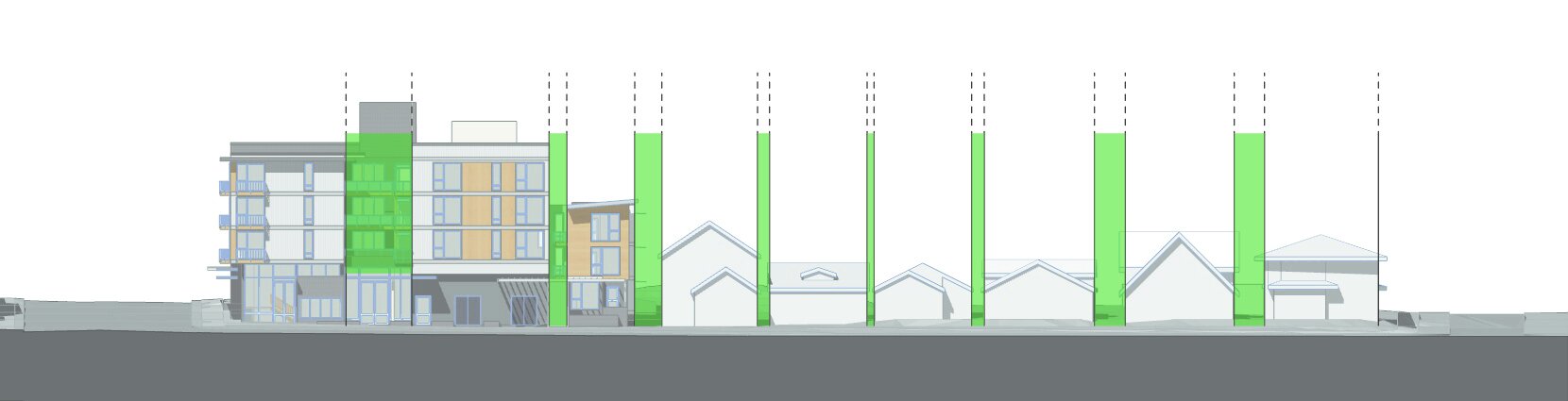

By breaking the project into two structures, the design team created another opportunity. The space in between the two structures, opened up light and air to units to the north and south and created a courtyard space at the center. These spaces also establish rhythm in the frontages to both Eastlake Avenue E and Fuhrman Avenue E. The break in the facade along Fuhrman Avenue E is extended via a breezeway through the larger structure, producing a portal to the water of Portage Bay for residents.

Early in the project, the team decided to recreate and improve the pedestrian access from the entry of University of Washington Bridge to the waterfront. The path residents had been using, was a poorly built wooden stair at the bottom of the sloped Red Robin parking lot. b9 architects began designing a public stair connecting Fuhrman Avenue E to Portage Bay below, to serve the community and create a landscape and trail buffer between the Robin’s Nest site and the bridge. Nine months into the design of this project, the city discovered a 24 inch water main running alongside the project below ground in between the property and the University Bridge. If the pipe would have been touched or moved and subsequently ruptured, the high water pressure released would have been catastrophic. Significant explorations determined that the pipe was only 4.5 feet below existing grade. These explorations combined with a careful shoring design and installation protected the pipe and the surrounding area, but impacted the scope of the pedestrian trail. Despite this complication the final stair creates a safe pedestrian trail that connects the lower street, Portage Bay Place E, to Fuhrman Avenue E above, providing a direct connection instead of forcing pedestrians to walk under the bridge where visibility on the one-lane, Portage Bay Place E was extremely limited.

When the project began the design and entitlement process, as a one-lane road, Portage Bay Place was thought to be a “named alley”, and so any parking proposed by the project would take access from that alley, and with the slope of the site, Portage Bay Place is the only feasible vehicular access point for the Robin’s Nest project. Due to its small size and a potential loss of improvised parking spaces inside the project’s setback, the neighboring community was concerned about the number of cars Robin’s Nest would add to the narrow road. During the Design Review process, Portage Bay Place was unexpectedly determined to be a street due to a mapping distinction discovered midway through the project process This resulted in many in the community arguing for the project to take vehicular access from Fuhrman Avenue E. A major complication, this led to a compromise with the city by which the project would widen the road surface and provide a vehicular turnout to address the narrowness and length of the one-lane, dead-end road. After substantial delays of the project, b9 took the initiative to present the compromise to the neighborhood and, after informing them of the proposed improvements along the project’s Portage Bay Place E frontage, reached a resolution that allowed the design to proceed.

In all, the client and design team embraced the opportunity to create a boutique solution that set new standards for a mixed-use multifamily building. The overall design, exterior material palette, exterior common spaces, provision of parking, unit mix, interior design, commitment to overall quality and high profile location make Robin’s Nest extremely unique in Seattle. Considered by many people as impossible to develop due to the steep slope and the City’s and neighborhood’s strong connection to the former restaurant, the site presented the team with multiple challenges along the way. The height measurement technique and restriction in the shoreline overlay, the high pressure water main, and the street improvements to Portage Bay Place all required the team at b9 architects to be adaptable. By responding to each moment with imagination and critical thinking, the team at b9 architects was able to design and help execute an excellent building that highlights the gorgeous views of Portage Bay and the University Bridge.